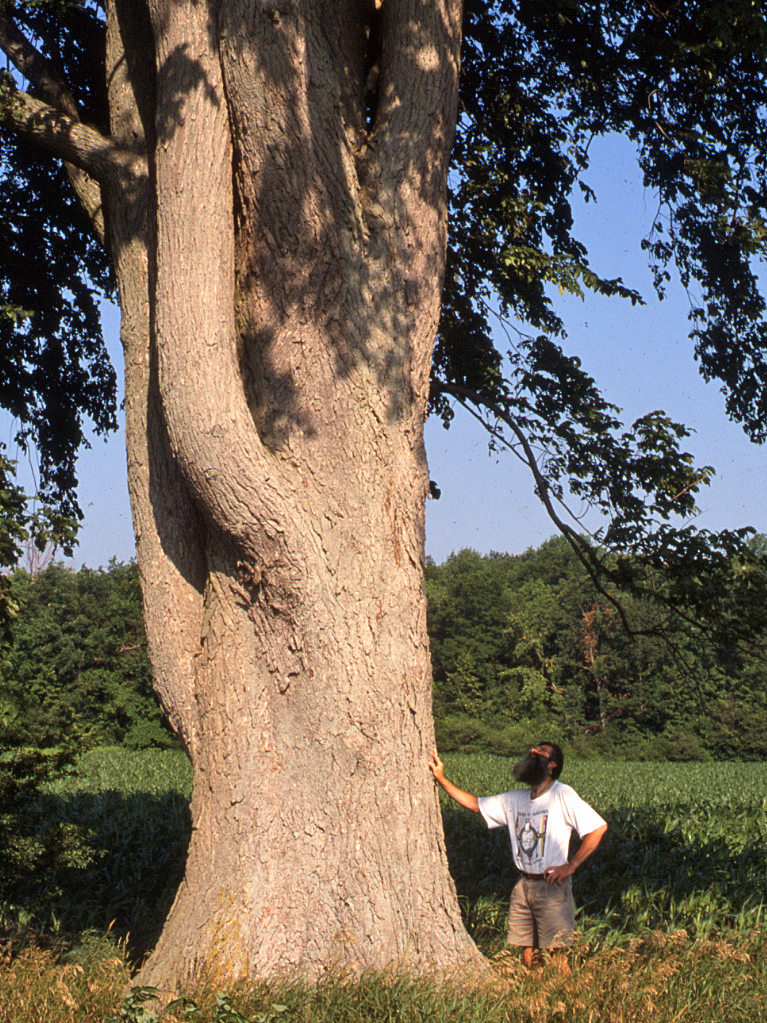

Until about the 20th century, American beech was the most common tree in the Maritimes. With porcelain bark and generous mast, this species was a key player in regional biodiversity, and a conspicuous member of any given stand.

But that’s no longer true, and hasn’t been since 1890, when the Beech Scale – an invasive European insect – was accidentally imported to Halifax Harbour. This insect slurps its living from the sap of beech trees, and plunders the sugars of the American beech so thoroughly the tree is left weak, and full of holes. Through these holes invade native fungi, infecting, stunting and deforming the tree from inside out.

Today, the American beech of the Maritimes are lepers, ravished by black rot and producing nuts only rarely, if at all. We call this condition Beech Bark Disease, the dual assault of scale and fungus, and it’s ubiquitous.

“Even in the Maritimes,” said Donnie McPhee, coordinator of the National Tree Seed Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick, “people have lost the ability to identify what a clean American beech looks like.”

But not everyone. In 2004-2005, as the Beech Scale expanded to untapped provinces and states, researchers with the Canadian Forest Service conducted a survey of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, discovering, to their amazement, that about 3.3 per cent of the regional’s American beech were entirely unscathed.

This wasn’t luck. Through one genetic quirk or another, these trees supported bark chemistry lethal to the invasive Beech Scale, killing any who attempted to slurp their sugars, and forestalling the incursion of fungus. In a forest ecosystem now flush with Beech Scale, these hardy survivors had the right stuff, to endure and reproduce, if only they weren’t so far apart.

McPhee was part of a joint effort, between the Canadian Forest Service and Parks Canada, to collect grafts from these unscathed tree (clones, essentially) and plant them together in three distinct groves, one each in Kejimkujik, Fundy and PEI national parks, where they’ve been quietly maturing since 2010. In 2022, they were old enough to produce a few beechnuts, but in time they’ll produce a lot more, seeds which will, hopefully, support the same resistance to Beech Bark Disease as their parents. From there, mass replanting becomes a possibility.

The problem is time, said McPhee. We should be able to breed trees the same way we breed potatoes, except potatoes doesn’t take 15 years to reach sexual maturity. Maintaining these groves is one thing, but holding onto the requisite people and funds for decades at a time is quite another. Shortly after these groves were planted, Parks Canada underwent a massive reduction in staff, and every ecologist with whom McPhee collaborated was suddenly gone. More have since been hired, and the groves are still being maintained, but for the moment, there’s no real plan for these American beech.

“The fact of the matter is,” said McPhee, “unless there’s money to be made from a tree species, it’s really hard to find the long-term funding to carry out a project like this. I absolutely worry about our forest ecosystems, and the rate at which things are changing.”

The Fallen

Tree breeding is not a new phenomena. Foresters have encouraged desirable traits in their woodlots for decades, and new varieties of apple are hitting the market all the time, but as the native trees of eastern North America are slowly obliterated by one invasive pathogen or another, the concept has garnered attention, albeit with very few precedents. One is the unfulfilled promise of the American beech, and another is the belligerence of the American elm.

At one time, American elm was our hardiest tree. It grew in soils wet or dry, acidic or alkaline, sunny or shady, disturbed or pristine, and was even a favourite of urban foresters, able to endure the compact soil and stuffy air of city centres. By the 1920s, it could have been argued the American elm was “overabundant,” rapidly recolonizing degraded soils in the wake of human industry.

This golden age ended abruptly, when an invasive fungus was introduced independently to New Jersey, Ohio and Quebec in the 1930s and 1940s. What we now call Dutch Elm Disease (DED) exacted a spectacular toll on the American elm, killing hundreds of thousands in a few short decades, reducing one of the toughest trees in eastern North America to an endangered species.

DED, on its own, is not especially dangerous. It’s lethality comes from its strangeness, appearing so unfamiliar to the immune system of the American elm that the tree overreacts, pre-emptively sealing off so much of its own circulatory system that it withers. DED, therefore, is one step removed from an autoimmune disease.

But as with the American beech, there were outliers, elms with a distinct genetic cocktail first appreciated by Henry Kock in the 1990s. At that time, Kock was a horticulturalist with The Arboretum at Guelph University, 400 acres of managed forest adjacent to campus, its grounds dedicated to research, education and conservation.

Kock kept coming across American elm who were, in spite of DED, healthy and hardy, gracing old farms and country roads. It was initially assumed these trees were just lucky, so isolated the fungus never reached them, but this didn’t add up. Kock spoke to farmers who originally had several dozen American elm, all of them dying to DED when the fungus rolled through, save one. These survivors hadn’t avoided DED. They had the right stuff.

Kock was a good scientist, and didn’t take these trees at their word. Instead he took their grafts, cloning each several times over, and bringing those clones to The Arboretum, where he and his protégé Sean Fox, alongside forest pathologist Martin Hubbes with the University of Toronto, put these trees to the test. One year they’d inject DED into their branches, the next year into their trunks. First they tried a mild strain, then a ferocious one, then both simultaneously. Year after year, these grafts were infected, and year after year, they shrugged the infection off.

“We have over a hundred mother trees that, for the past 20-25 years, we haven’t been able to kill,” said Fox, now a horticulturalist and senior research associate with The Arboretum.

The right stuff, in the case of these American elm, manifests as a measured response to infection, encoded somewhere in the tree’s genome. They resisted DED without going nuclear, losing a leaf here or a branch there, but ultimately defeating the fungus. Kock and Fox confirmed this trait in 110 mother trees across Ontario, from whom they’ve taken 450 grafts, now growing at The Arboretum.

“Henry told me he was never going to see the end of this project,” said Fox. “I won’t either, because I think its success will be multiple generations past us, when this tree is naturally regenerating on the landscape.”

And that will take more than clones. Genetic diversity in the only reason DED-resistant American elm exist, allowing just enough variation between individuals that, by chance, 110 trees across Ontario were ready for the fungus before it arrived. Replanting Ontario with tens of thousands of grafts from those same 110 trees – a homogenous blitz of clones – might allow this tree to gain ground in the short term, but would rob the species of crucial genetic diversity, leaving the American elm vulnerable to whatever comes next.

Holding onto diversity, said Fox, will require sex, and lots of it. Their 450 grafts have recently begun producing seed with one another, and the resulting seedlings should possess some degree of DED resistance, but there are no guarantees in sexual reproduction. Some will resist the pathogen like their parents. Some won’t. Some will be better adapted to drought, cold and predation from insects, others worse. Diversity can be expensive, but it’s the species’ only real hope.

“Holding onto that diversity is best,” said Fox. “We’re going to be getting this seed out to restoration nurseries, to conservation authorities, to national and provincial parks. Plant a thousand of them, confident that some will become that next generation of healthy tree. Over time, we hope to see those trees sharing pollen with each other and, over multiple generations, start to see 100-200 year old elm trees supporting Baltimore orioles and all sorts of wildlife.”

Inventing Resistance

Not all trees have the raw recovery potential of the American elm or American beech, either because the gene pool is too small or inborn resistance wasn’t there in the first place. Or both.

The American chestnut fits this description. After the introduction of Chestnut Blight to New Jersey in 1876, this tree was eradicated across its entire range, from Mississippi to Maine, a stretch of eastern North America in which it accounted for a quarter of all trees. There were no inexplicable survivors, no harbingers of the right stuff. If a chestnut was alive, it was either a crossbreed with a Chinese or Japanese chestnut (both of whom are naturally resistant to blight), or just lucky.

So when the Canadian Chestnut Council (CCC) ended up breeding the species anyway, it was by accident. Their plan was intentionally to cross pure American chestnuts with their Chinese and Japanese cousins, and then “backbreed” those hybrids with pure Americans, ultimately producing a tree with all the physical characteristics of the American chestnut, but the blight resistance of their Japanese and Chinese forebears.

But you can’t do good science without a control group, so project founder Adam Dale, with the University of Guelph, also crossed 26 pure American chestnuts with each other, the healthiest specimens known in southern Ontario. The resulting 643 seedlings became his control group, against which he would measure the progress of his hybrids. But as the generations rolled by, and the healthiest were bred with the healthiest, Dale discovered something extraordinary. His control group of pure American chestnuts was developing blight resistance at roughly the same rate as his crossbreeds.

“They’ve got something,” said Dragan Galic, the University of Guelph researcher who took over the breeding program from Dale. “There’s no doubt in my mind.”

While Galic still maintains the hybrids, the “control group” is now his primary focus, presently in its third generation. Some of these chestnuts have survived with lethal doses of blight for 20 years now. Some, the CCC expects, could hold out over a century.

Exactly how they’re resisting Chestnut Blight is an open question, but Galic suspects several mechanisms are working in concert. The right stuff, he suggests, has three separate parts – the integrity of a tree’s bark (preventing initial infection), the ability of trees to callus (isolating infection), and phytoalexins, a class of antimicrobial compounds used by trees to combat infection. Strength in any one of these categories might not save a chestnut, but breed all three into a single tree, and you have something approaching the right stuff.

If Galic is correct, then the CCC didn’t so much discover blight resistance as invent it, mixing the genes of a precious few trees and coming away with a workable solution. In another two or three years, the strongest individuals from Galic’s third generation will breed to produce a fourth, ready, he hopes, for distribution in the wild.

The right stuff came at a heavy cost to the American chestnut. Their gene pool of 26 trees was small to begin with, and successive generations have narrowed it further. The control group’s fourth generation might well be resistant to Chestnut Blight, but between them will be effectively no diversity.

The only safeguard, once again, is sex, lots and lots of open pollination with the few wild chestnuts still standing. The CCC will plant their seedlings in the company of isolated elders, pairing the diversity lost in their breeding program with its hard won genetic resistance. If all goes well, Ontario’s chestnuts will have a fighting chance. Resistance breeding is an unproven science, requiring so many decades, dollars and careers that, to date, it hasn’t yet worked, but pioneers like the American beech, American elm and American chestnut are slowly proving the concept, their lessons already being applied to other trees in abject peril, like the Eastern hemlock, Black ash and White walnut. Across eastern North America, programs young and old remain in search of the right stuff.

Zack Metcalfe is a freelance journalist, columnist and author based in Salmon Arm, BC. This article was originally published with Rewilding Magazine.

Leave a comment