Since spring of 2023, over 7,000 Albertan homes have gotten their power from a shed north of Medicine Hat.

Inside this shed are 38 shipping containers stacked on a dirt floor, and inside these are polyethylene tanks of electrolyte, absorbing excess power from the solar farm outside and discharging to the grid after dark. Together they provide 8.4 MWh of electrical storage capacity, and they do so without lithium, cobalt or manganese. Litre for litre, they’re mostly water.

Redox flow batteries are not new. They appear in the literature as early as the 1950s, and by the 1970s, no less than NASA was slapping together prototypes. Rather than storing electricity in solid electrodes (ie. lithium-ion), flow batteries use positively and negatively charged liquid electrolytes, pumped from their separate tanks through “cell stacks,” where they exchange ions through a membrane, and electrons through copper wire. In chemical terms, one electrolyte “reduces” while the other “oxidizes,” hence the term “redox.”

There are as many flow batteries as there are electrolytes, provided the pair being used have enough reactivity and voltage between them. NASA’s prototype used iron and chromium, while others have experimented with bromine, tin, titanium, uranium, neptunium, plutonium and americium, all dissolved in solutions of acid and water.

“There are pros and cons to every chemistry,” said Marc-Antoni Goulet, assistant professor of chemical and materials engineering with Concordia University, Quebec. But in general, he said, redox flow batteries have very low energy density, storing about one tenth as much power per unit volume as lithium-ion. So to be useful, they need to be big, and heavy.

“Never say never,” said Goulet. “I think there’s room for improvement by maybe a factor or two or three, but is it ever going to be as energy dense as lithium-ion? I don’t think so. It’s very unlikely that something floating around in water will ever have the energy density of a solid electrode.”

Only one redox flow battery ever worked well enough to be fully commercialized, developed by Australian chemical engineer Maria Skyllas-Kazacos in the early 1980s. This uses vanadium – number 23 on the periodic table – in both positive and negative electrolyte, cycling through four separate oxidation states during charge and discharge, two on either side.

It’s this, the all-vanadium redox flow battery, occupying the shed north of Medicine Hat, balancing the intermittent generation of the 14 MW Chappice Lake Solar+Storage Project with the needs of the provincial electrical grid. They are the only redox flow batteries deployed at scale in Canada, and they were put there by a Canadian company.

Let There Be Solar

From the very beginning, redox flow batteries were designed with grid-scale renewables in mind. NASA’s investigations into the iron-chromium flow battery were in direct response to the 1973 oil crisis, in hopes that intermittent solar power, thus stored, could fill any forthcoming gaps on the electrical grid.

“They are very well suited to this kind of application,” said Edward Roberts, professor of electrochemical engineering with the University of Calgary.

That’s because redox flow batteries are incredibly easy to scale. The capacity of a lithium-ion battery, he said, is restricted by the physical size of its electrodes, and as these get larger, so must the battery. No single component can be independently scaled up or down, such that doubling lithium-ion storage capacity means doubling the number of lithium-ion batteries. At megawatt scales, this gets inefficient, and expensive.

In a redox flow battery, however, additional storage capacity can be had for a song – just add electrolyte. Cell stacks, plumbing and wiring can all remain the same, provided you attach a few more tanks. By the same token, said Roberts, the rate at which flow batteries discharge power can also be scaled up or down – just add or remove cell stacks. Most grid-scale lithium-ion is restricted to a 4 hour discharge window, whereas flow batteries can be customized for 4, 8, and even 18 hours, allowing stored renewables to trickle onto the grid as baseload, rather than flood on during peak demand.

It’s at scale, and over long storage durations, that the benefits of redox flow batteries become pronounced, and while renewables eventually created precisely this market, they didn’t do so right away. The all-vanadium flow battery was patented in 1986, while wind and solar didn’t justify grid-scale storage until the 21st Century.

“It’s only recently, with the increasing penetration of renewables, that there’s been a market pull for vanadium redox flow batteries,” said Roberts. “One might expect them to become ubiquitous now.”

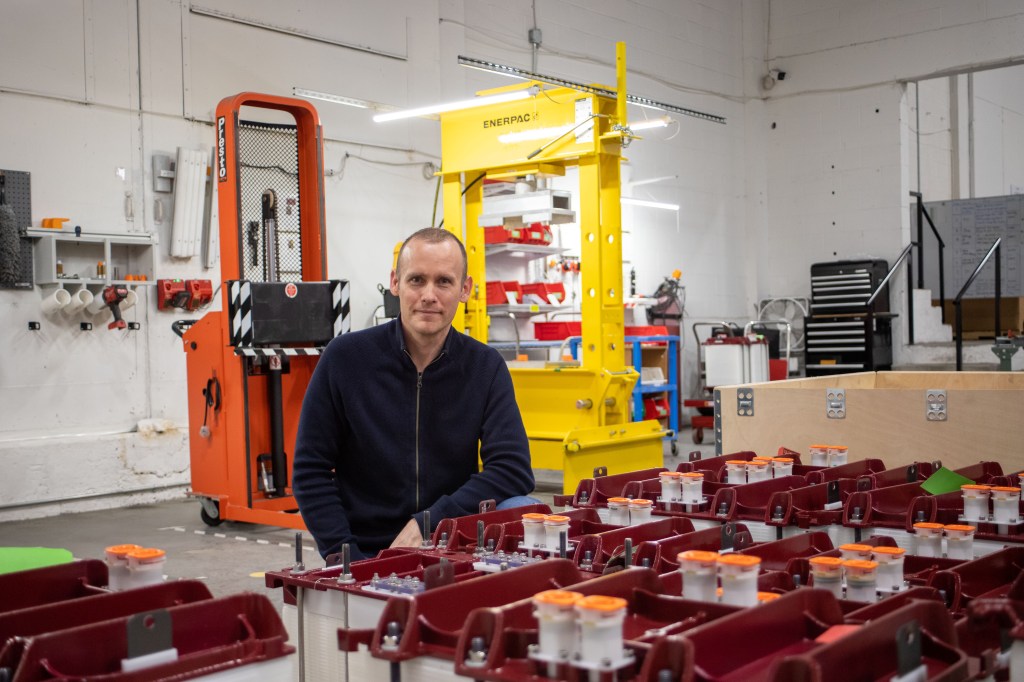

Matt Harper’s an engineer by training, and began his flow battery career in 2005 with VRB Energy, the original licensee of the all-vanadium flow battery in North America. Harper followed this license when it was sold to Prudent Energy in 2009, then established his own company – Avalon Battery – in Vancouver in 2013.

“What we saw that year,” said Harper, “were some really interesting opportunities emerging here in North America. Utility scale solar was going through an absolutely transformational shift, and I remember looking at that and thinking our batteries could be a really good fit.”

He also felt that up to that point, vanadium flow batteries were manufactured all wrong for a marriage with solar. Batteries built in the United States at that time for multiple megawatt hours of storage, he said, ended up looking like small chemical plants – electrolyte silos, concrete foundations, etcetera – for which contracting and permitting was slow.

“They took two and a half years to build,” said Harper. “Conversely, solar farms were being rolled out in the megawatts per week. We realized that if we were going to have a place to play alongside solar, we were going to have to come up with a fundamentally different architecture for the battery.”

Avalon Battery merged with the UK-based redT energy in 2020 to become Invinity Energy Systems, and in 2021, this joint venture deployed the VS3 all-vanadium flow battery, designed with two cell stacks suspended overtop electrolyte tanks. These are typically sold by the shipping container – six individual batteries wrapped in a steel shell 2.5 metres tall and wide, and 6 metres long, each weighing 24,600 kilograms with a total storage capacity of 230 kWh. They’re easily shipped, easily stored, easily networked, and can hold power on day one.

These “six-packs” might have low energy density relative to their size, said Harper, but wherever bulk isn’t an issue – on a solar farm, say – they can be packed cheek by jowl, and stacked several high, putting every square centimetre of available space to work storing power. The same cannot be said for grid-scale lithium-ion, whose individual batteries must be spaced a certain distance apart to prevent thermal runaway, and to contain the fires and explosions to which lithium-ion is prone. Flow batteries, by contrast, cannot burn, and operate at much cooler temperatures.

“The technology is fundamentally less energy dense than lithium-ion on a watthour per kilogram or watthour per litre basis,” said Harper, “but per acre, it’s equivalent to, or in some cases slightly better than, what you’d see with lithium-ion.”

The drawback is price. While vanadium is the 13th most common metal in the Earth’s crust – more common than copper or nickel – it rarely occurs in large deposits, and very little is mined directly. Most reaches the market via iron mining, of which vanadium as a secondary product. It’s primarily produced in China, Russia, South Africa and Brazil for use in steel manufacturing, and comes with significant price volatility.

Because vanadium electrolyte represents 30-40 per cent of the VS3’s product cost, said Harper, their batteries are roughly twice as expensive as lithium-ion per installed kilowatt hour of storage capacity. This is not the case for flow batteries manufactured in China, where vanadium is sourced cheaply, and gigawatts of flow battery storage are installed each year.

Even with the relatively high price of the VS3, said Harper, it remains cost competitive with lithium-ion over its lifetime, if for no other reason than because that lifetime is so long. Vanadium electrolyte – essentially unchanged since its initial development in the 1980s – is so extraordinarily stable that it will not degrade over time. This means that any loss in the VS3’s storage capacity (less than 0.5 per cent per year) is entirely a consequence of aging hardware.

The VS3 is rated for at least 25 years of continuous operation – the approximate lifespan of most solar and wind farms – and can be fully charged and discharged any number of times without hastening capacity loss. After those 25 years, the battery in 99 per cent recyclable by weight, its electrolyte (the most expensive single component) immediately ready for service in a new battery.

Grid-scale lithium-ion, by contrast, is typically rated for no more than 15 years, loses capacity much faster, is limited in how deeply and how often it can be discharged, and is difficult to recycle. These factors bring the VS3’s “levelized cost of storage” – price per megawatt of delivered electricity over the battery’s lifetime – below that of lithium-ion, said Harper.

Today, Invinity has field offices in California and London, and manufacturing facilities in Vancouver, Scotland and China. They have about 80 megawatt hours of storage capacity installed globally, with another 100 megawatt hours in the pipeline, but apart from Chappice Lake Solar+Storage, none of this capacity is Canadian. Harper expects this to change as more renewables enter the mix, and Invinity already has its eye on wind and tidal projects in Nova Scotia, but in most jurisdictions, the longevity and scalability of the VS3 – or Invinity’s new battery, Endurium – haven’t yet justified the high cost of installation.

For his part, Marc-Antoni Goulet expects flow batteries will make more sense in some provinces than others, if and when the price comes down.

“BC and Quebec don’t need flow batteries all that much,” said Goulet, “because we have a bunch of hydroelectric power, which already behaves like a battery – cut back the flow of water when you need to store it and let it out when you need to use it. No, it’s all the other provinces, like the prairies, the maritimes, the territories – anywhere you could install more intermittent renewables – who could benefit from a cheap flow battery technology.”

An Unproven Alternative

Both Marc-Antoni Goulet and Edward Roberts point to the price of vanadium flow batteries as the limiting factor in their widespread adoption, and Roberts has researched the possibility of making them cheaper since the early 1990s.

“Although I’m not sure how successful we’ve really been,” he said.

Invinity hopes that economies of scale – and the potential of sourcing vanadium from petrochemical waste – will bring their batteries within 1.2-1.5 times the installed cost of lithium-ion, but several labs are getting away from vanadium altogether.

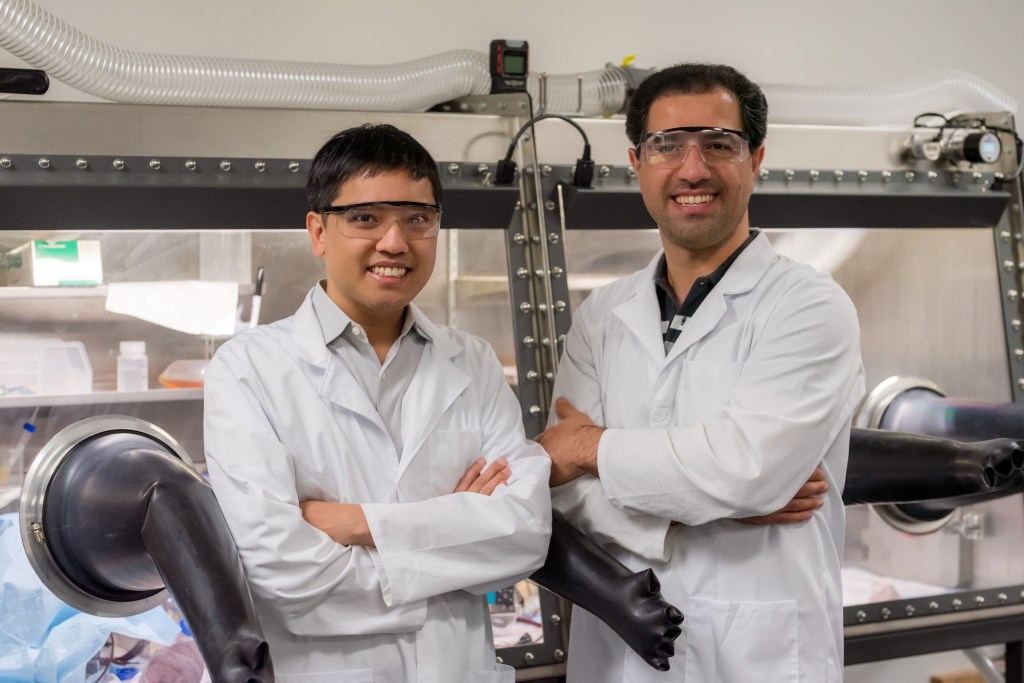

Michael Aziz is a professor of materials and energy technologies with Harvard University, and fifteen years ago, he pioneered the idea of stocking flow batteries not with vanadium, but with organic molecules.

“I noticed that some groups were successfully using organics in fuel cells,” he said, “and a flow battery is basically a fuel cell that can run forward and reverse.”

The trick was finding an organic molecular which could tolerate life in a battery without rapidly decomposing, and which could hold a charge. His search led to quinones, a class of molecules used, among other things, for dying fabric. While several are the subject of active research, Aziz and colleagues struck upon DCDHAQ (1,8-dihydroxy-2,7-dicarboxymethyl-9,10-anthraquinone), a quinone cheaply sourced from coal tar and petroleum aromatics, and which, when dissolved at sufficient concentrations, produces an electrolyte with energy densities on par with vanadium.

DCDHAQ does degrade over time, just very slowly, and at a rate unaffected by how many charge-discharge cycles it’s exposed to. In rough figures, a flow battery using this quinone can be expected to lose 3-4 per cent of its capacity over 20 years, a lose easily supplemented with new electrolyte.

“We are essentially a drop-in replacement for vanadium,” said Eugene Beh, CEO and cofounder of Quino Energy, a startup commercializing Harvard’s work on DCDHAQ.

By “drop-in replacement,” he means that flow batteries manufactured for vanadium electrolyte will run just as well, without any reengineering, on Quino’s organic alternative, one which can be manufactured anywhere there are fossil fuels.

“I’ve been going to these companies and telling them, you don’t need to change all your engineering, or give up all the hard work that’s already gone into your batteries,” said Beh. “I’m just asking you to use a cheaper electrolyte.”

Cheaper in theory, anyway. Quino Energy manufactures its DCDHAQ electrolyte at a dedicated facility in Buffalo, New York, and by the end of 2025, Beh expects to achieve price parity with vanadium electrolyte. By 2029, once supply chains are firmly established, he plans to be a quarter the price, allowing flow batteries to be cost competitive with lithium-ion at installation.

“The fact of the matter is,” said Beh, “renewable power generation, plus storage, is the cheapest energy out there. Unless government puts its thumb hard on the side of fossil generation, solar and wind are already unstoppable, and they come with the need for storage.”

The “organic aqueous redox flow battery” has not yet been demonstrated in systems over 100kWh, but larger systems just mean more cell stack, and more electrolyte tanks. Matt Harper called organic electrolytes “unproven” and “promising,” while Michael Aziz and Eugene Beh expect vanadium’s days are numbered.

“We’ve achieved this holy grail of having a long lifespan while also being very cheap to manufacture,” said Beh. “Soon, we think, the default chemistry for flow batteries isn’t going to be vanadium, but our organic electrolyte.”

Zack Metcalfe is a freelance journalist, columnist and author based in Salmon Arm, BC. A version of this article was originally published with Canada’s National Observer.

Leave a comment