In May of 2023, biologist Chelsea Greer was bent over a camera trap, one of several dozen scattered over 200 km2 of British Columbia’s Lower Mainland. This particular trap hugged a river known for Sockeye salmon, its degraded spawning beds slated for imminent restoration by the local First Nation, but Greer wasn’t after fish. This trap was for wolves.

“They’re a sensitive species,” said Greer, wolf conservation program director with the Raincoast Conservation Foundation. “Put anything novel in their environment and they’ll notice.”

Her traps were no exception, but the wrong camera might click while turning on and off, or emit flashes of infrared light invisible to the human eye, but not to a wolf’s. All of this might cause undo stress, so Greer chose her gear accordingly – inconspicuous, if not invisible. Her goal was a non-invasive research program, allowing her to answer basic questions about a given population without the live-trapping, tranquilizing, tissue sampling and radio collaring pervasive in so much wolf research to date.

“We’re not just considering their welfare,” she said. “When you impact the behaviour of your study species, that impacts the reliability of your data.”

To this end, her camera traps were paired with acoustic recorders, so the wolves in her footage might eventually be linked to their calls. She also collected scat opportunistically, for followup fecal and DNA analysis. It would all paint a picture in time, but on that day in May, her best data didn’t come from scat, camera or recorder. It came from the involuntary gasp of a colleague standing behind her.

Greer turned in time to see what her colleague had seen – a very wet wolf standing upstream, its black fur waterlogged and tight to the skin, giving an otherwise formidable creature the baring of a greyhound, short and slim. Then it was gone, sliding into the understory while emitting a curious bark. This, said Greer, was a “bark howl,” an alarm call typically used in “homesite area,” where wolves keep their pups.

In those few seconds, Greer learned two very important things – that wolves once again built dens in BC’s Lower Mainland, and that she was standing on one of them.

Elk Lead The Way

Call him Elder, because the 200 km2 studied by Greer are on his traditional territory, and that traditional territory is not especially large. As a prominent member of a Coast Salish First Nation, his real name amounts to a roadmap, and he’s determined to keep the wolves on his land safe from hunters, trappers and tourists alike, hence the pseudonym, and the lack of specific locations in this article.

Elder’s never seen the fjords of Norway, but his home is often compared to them – mountains grey and white swooping skyward over a southern lake and northern river valley. Giant Western redcedars can still be found in its unlogged corners, and its glacial streams boast famous runs of Sockeye, Chinook and Coho salmon. Protecting the land and its wildlife is among Elder’s responsibilities, but in spite of him, things are changing.

“I remember swimming in the lake when I was six years old,” he said. “You’d jump off the dock and swim for shore as fast as you could. Stay in there for any length of time and you’d get hypothermia.”

Now children swim comfortably in the very same water, the glaciers giving life to these lakes and rivers receding entire miles in Elder’s lifetime. The warmer water complicates salmon spawning, as do landslides from clearcutting and competition with invasive bass. He and his nation have worked very hard to keep the salmon running.

“There’ve been times when no salmon showed up, and those were sad days,” he said. “You’ll hear me get emotional when talking about it…choked up.”

Wolves were extirpated from BC’s Lower Mainland – and therefore Elder’s home – sometime in the 1950s, victims of rampant hunting, trapping, poisoning, and the concurrent extirpation of Roosevelt elk. But the elk came back, reintroduced to several dozen forests throughout the Lower Mainland since the 1980s. The few dozen released on Elder’s land in the early 2000s now number in the hundreds, welcome game when the salmon runs fail.

And wolves followed the elk, or so it’s generally assumed. At first they were rumours, then black and tawny blurs in grainy smartphone photographs. The veil was lifted in 2021, when Elder and council partnered with the Raincoast Conservation Foundation, a charitable non-profit conservation science organization active across the Pacific Northwest. Greer’s camera traps went live that same year.

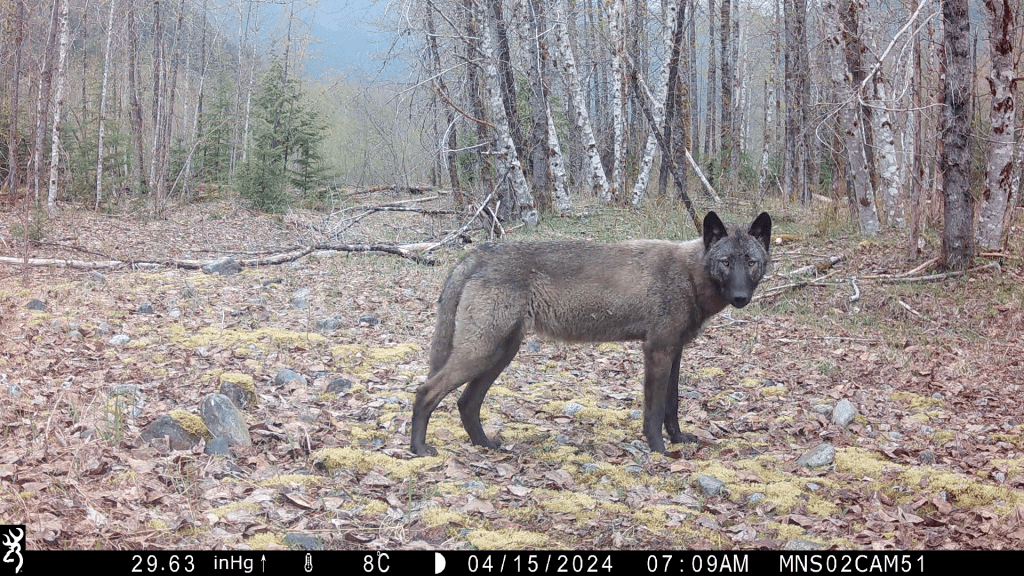

What they revealed was a resident pack – the first in living memory – with around six adults at any given time. Some come and some go. Some pups reach maturity and some don’t. Some avoid Greer’s traps so studiously she can’t tell them apart, while some regard them with benign indifference. By far the most commonly recorded is the pack’s breeding female, black, with a greying muzzle and seasonal hair loss along her tail, perhaps because her pups chewed it off each spring.

Greer’s recorded them passing through cutblocks, escorting pups, chasing down deer and wading glacial streams. Their scat betrays a diet of salmon, deer, mice, beaver, muskrat and, naturally enough, elk. What it hasn’t betrayed – because genetic analysis is forthcoming – is where these wolves came from.

When wolves disperse into new territory, it’s nothing for them to travel a thousand kilometres and more. The pack of the Lower Mainland could hale as easily from the Rocky Mountains in the east as from the Great Bear Rainforest in the north. Paul Paquet, a senior scientist with Raincoast, has studied wolves across North America and Europe since 1979, and to his eye, these ones are strange.

“Something seems a little off to me,” he said, noting thinner coats and longer tails than he’s accustomed to. These quirks, however subtle, might suggest a trace of coyote ancestry, though this is rare in the west.

“They’re likely a mix of Coastal and Rocky Mountain wolves,” he said, the province’s two main “ecotypes,” colliding by chance in the Lower Mainland.

The Only Good Wolf

To be a wolf in British Columbia is bad for one’s health. The species has been formally persecuted since 1900 through bounty and predator control programs, and as recently as the 1960s, poisoned bait was dropped on protected areas and ranchland, laced with strychnine, cyanide, and Compound 1080.

About a thousand wolves are still killed in BC every year, the majority by hunters and trappers who do not require a species-specific license to kill them, and who can do so for the majority of the year in the majority of jurisdictions. Even where bag limits do exist, reporting the death of a wolf is rarely mandatory. Such “open season” regulations are why Elder and council keep their wolves a relative secret, protecting their pack from a very old adage – the only good wolf is a dead wolf.

“There’s concern from hunters who don’t like the competition for elk,” said Elder. “Some said we should shoot all the wolves, but I said no. Wolves have the right to eat, just as we do.”

The provincial government also kills wolves from helicopter, putting down packs with the stated intention of recovering endangered Mountain caribou. This program, officially launched in 2015 and since expanded to the domain of several herds, remains controversial on moral as well as scientific grounds. Whether or not wolf culls benefit caribou in the near or long term is the subject of ongoing debate in the literature, and a common criticism is that unabated habitat loss, not wolves, is in fact the primary driver of caribou decline.

Wildlife biologist Gilbert Proulx, director of science with Alpha Wildlife Research & Management in Sherwood Park, Alberta, has studied wolves since the 1970s. He said that if wolves play any part in the decline of caribou, this, too, is a consequence of habitat loss, be it from oil, gas or forestry. By blazing roads and trails into muskegs (in the Boreal) and into alpine forests (in the Rockies) these industries give wolves unnatural access to caribou habitat, specifically the habitats they couldn’t otherwise penetrate.

“The roads are the problem,” said Proulx.

Greater ecological harm comes from the absence of wolves than from their presence, he said, recalling a wolf cull in the Cooking Lake-Blackfoot Provincial Recreation Area east of Edmonton, Alberta, carried out in the 2010s. Prior to the cull, invasive wild boar was conspicuously absent from the recreation area, though plentiful on neighbouring lands.

“And then boom,” he said, “they were all over the place, and that only happened after they destroyed the wolfpack.”

That wolves might prevent incursions of invasive species is, for the moment, anecdotal, said Proulx. Less so is their ability to suppress disease among their ungulate prey, by preferentially killing the sickest members of a given herd. Chronic Wasting Disease is a timely example.

“I only hunt where wolves are present,” he said, “because, odds are, the deer I take will be in perfect health.”

The power of wolves to moderate ecosystems is well demonstrated. By hunting large ungulates, be them deer, elk or moose, wolves prevent runaway population growth, which in turn prevents overgrazing, making herds less susceptible to mass starvation over lean winters. Not only are ungulates healthier and stabler in the presence of wolves, but they’re also more cautious, avoiding open spaces in which they might otherwise linger to the detriment of saplings. Resulting reforestation has, at times, been explosive.

Eruptions of aspen and willow followed the return of wolves to parts of the Rocky Mountains from which they’d been exterminated, said Proulx, and the same was observed in Yellowstone National Park following their reintroduction. More trees meant a boom in beaver colonies – those of Yellowstone increased by a factor of 14 – with knock on benefits to the watersheds in question. Songbird diversity and abundance also increased in the presence of wolves.

“We’ve shown that in many places, like Jasper, Banff and Yellowstone, the coming back of wolves has, overall, contributed to the ecosystem,” said Proulx. What changes they’ll bring to the Lower Mainland remains to be seen, he said, because the Coastal Mountains are so different from The Rockies, but he doesn’t doubt the importance of wolves.

“I really believe that the moment you eliminate large predators from a natural community,” said Proulx, “you’re creating problems.”

The Wet Wolf

There are times when Elder can’t catch his own salmon, even now that so many have come back, even when restored spawning beds are teeming with them. This he accepts, to a point. That salmon are doing poorly in much of the Pacific Northwest, and that his salmon are not easily disentangled from regulations protecting all salmon, is enough to stay his net.

“We refer to them as our salmon family,” he said, with all the responsibility that implies.

But when it comes to ceremony – specifically the First Salmon Ceremony common among Coast Salish First Nations – Elder has been…creative, risking fines to catch the single Sockeye this ceremony requires every year, or travelling great distances to acquire a Sockeye born in his territory, but caught somewhere else.

Cutting through this legal theatre, are the wolves. Via Greer’s camera traps, Elder has watched the modest pack recolonizing his home bobbing for Sockeye, catching the very fish he can’t, in the very streams he and his people restored.

“I didn’t even know wolves were fishermen,” he said. “I just love it.”

He also loves the revivals documented in places like Yellowstone, and earnestly hopes this pack will do some of the same for his home. And if the rumours are true, this pack might not be alone. Greer is in discussions with the First Nation immediately adjacent to Elder’s, where sightings of wolves are building to a critical mass. Nothing’s settled yet, but her research program might expand in that direction, confirming another pack in the Lower Mainland, and determining what relation, if any, it has with the first.

“All the wildlife out there,” said Elder, “swimming, flying, walking on all fours, they’re our family. The salmon are here. The wolves are here. The elk are here. We’re here. I think we can all live together.”

Zack Metcalfe is a freelance journalist, columnist and author based in Salmon Arm, BC. A version of this article was originally published with Rewilding Magazine.

Leave a comment